Week 7: 12th - 18th June (Activities: 3.5 & 3.6)

Strategy and power are often seen as related, not least since ‘powerful people’ seem to have strategic influence while formal organisation strategies can have powerful effects on employees. Power is a complex concept and closely related to understandings of authority, control, influence, politics, conflict and resistance, and to particular roles such as leader or expert. A general understanding of power reflects the idea that an individual (or group) can control or influence the behaviour of another individual (or group), with or without their agreement. Issues of power in organisations are generally concerned with access to resources and controlling who gets what, when, where and how. Power is embedded within both strategic and operational issues, but also operates at a micro or interpersonal level. Indeed, according to Lukes (1986), in providing you, the student, with a definition of power, I, the author, am establishing the basis of a power relationship between us.

In discussing strategy and in exploring the ways in which strategy is developed, you have no doubt already thought about organisational politics and power relationships. Before we explore this in more detail, the activity below encourages you to reflect on these understandings.

Activity 3.5: Reflections on power (90 minutes)

Strategy is often presented in economic terms and as the outcome of a rational decision-making process that determines the best way forward. Yet power is manifest in the processes of formulating strategy as different options are debated and certain viewpoints are accepted (and others rejected). As Vince (2014) states, his paper aims to be provocative and introduces some different perspectives on power. You will consider these in more detail in the next section.

Different conceptions of power

As introduced earlier, there is a general understanding of power as being implicit in our day-to-day organisational lives and as necessary for getting things done. Here we unpack understandings of power a little more.

Fulop and Linstead (2009, p. 282) offer four images to represent different perspectives on power, which are shown in the left-hand column of Table 3.2. The right-hand column describes the basis of these perspectives.

- Legitimate power is regarded as a form of power that stems from the position held. It derives from the assumption that an individual or group has the right to make demands and expect compliance from others (e.g. managers with subordinates).

- Reward power derives from the ability to offer a reward or compensation in return for obedience and compliance. In organisations the most common and recognised form of reward is monetary pay. Employees are expected to follow the manager’s orders and direction because they get paid for it.

- Coercive power derives from the ability to punish those who do not comply. In organisations the threat of losing one’s job or being penalised or punished in some way allows managers to exercise a strong influence on employees.

- Expert power derives from one’s expertise, knowledge and skills. It is not associated with a specific status or position; individuals with expert power can be positioned at all hierarchical levels. It is their specialised knowledge or skill that allows some individuals to exert influence on others.

- Reference power is a type of personal power and is generally associated to the individual’s charisma, attractiveness and worthiness.

Drawing on the above categorisation (which was introduced in B863 The human resource professional), Harrison (2009) advises HRD practitioners that they need three types of power, listed below. An example scenario is used to illustrate these different elements.

Resource power

This relates to the ownership of different types of resources (and therefore is related to reward power, above). It is suggested that HRD practitioners should ensure they are aware of all the different forms of resources required to implement an HRD strategy and understand where the power lies in terms of mobilising these resources at the right time.

Example scenario:

A large financial organisation had spent many months planning the implementation of a new software system that would help financial advisors based in branches assess loan and mortgage applications during an advice session with the customer. This would provide a high level of customer service and, critically, a competitive advantage, in terms of ensuring that loan applications were converted into sales. There was a detailed HRD strategy that accompanied this change as it involved a fundamental shift in the role of the advisors. The strategy was, in part, influenced by the regulation of financial advice in the UK. In summary, each financial advisor required an extensive period of classroom-based training before they used the software and ongoing coaching after its implementation. This approach had been approved and costed within HR and by the IT department, which needed to provide the equipped classrooms. However, those involved had overlooked the need for the branches to authorise the release of the financial advisors to attend the classroom-based training; they had assumed that the branch managers would approve their training requests given the overall importance of the project to the organisation. However, the branch managers felt that the time required for classroom-based training was excessive. Furthermore, losing financial advisors to training would impact the monthly performance targets that each branch manager was held accountable for. What happened in many cases was that the branch manager decided to authorise only one financial advisor to attend the training, on the basis that they could then come back to the branch and teach the others how to use the system. Those developing the HRD strategy for the project had overlooked the critical resource of ‘trainee time’ within their plan and not considered who held the power over this resource.

Position power

This relates to the category of legitimate power, above. HRD practitioners must understand where and how critical decisions regarding HRD strategy will be made, and, crucially, who the gatekeepers are who might allow them access to participate in these decision-making conversations and events. This is often discussed as the right of HR practitioners to have a ‘seat at the table’, to be involved in senior management decision-making in organisations.

Example scenario:

Continuing from the example above, issues relating to the resources allocated to different groups of users of the new computer system were also closely related to position power. This had an impact within the project team who were planning the implementation. For much of the project, those responsible for designing and developing the training were not invited to the project management meetings. The overall project manager had an IT background and placed most importance on those who were developing, testing and implementing the software products. Those working on the training for the new system found it difficult to get invited to meetings or to get issues of concern placed on the agenda. Indeed, it is possible to speculate that this is perhaps one reason that the previous scenario regarding ‘trainee time’ arose, as insufficient management attention was given to discussing people issues. About six months before the implementation a new manager started work on the project and was given responsibility for training. This manager had come from a previous successful IT project and was given a position on the senior management team based on their prior reputation. With the new manager in this position, key issues were able to be brought forward for discussion at the meetings and the training team found the issues they had been struggling with for some time were finally being discussed.

Expert power

This relates to the power associated with the perception that others have of an individual as an expert in a particular area and the extent to which they can then influence decision making, here in a strategy context. To some extent this is to do with ‘real’ knowledge and expertise but it is the perception of expertise that is critical here.

Example scenario

Extrapolating from the above scenario, the previous experience of the new manager was one of the reasons that they were suddenly ‘given’ position power. In this case, the manager had also recently completed an MBA at a prestigious business school. This happened to be the same business school that a number of senior managers had attended and therefore was perceived as being associated with access to expert knowledge. As can be seen as this scenario has been extended, these different conceptions of power can be closely related.

A relational view of power

Harrison’s summary and the examples provided earlier are based on the idea of power as a possession. As both the earlier reading by Vince (2014) and Fulop and Linstead’s (2009) list reflect, an alternative conception of power arises if we take a relational perspective. As Vince highlights, power is ‘about a range of different forces or dynamics that are integral to people’s experiences and to organizing processes. These dynamics are within the individual, between the self and others, and generated in groups; they inform, create, and constrain organizational behaviour, structure, and action’ (2014, p. 410).

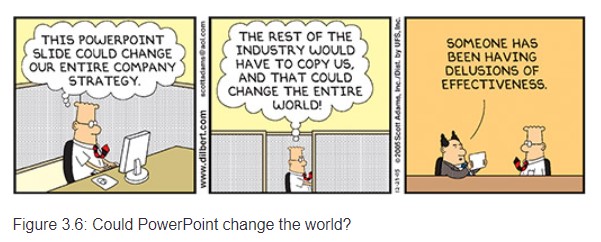

This perspective can be illustrated by an intriguing study on the role of technology in strategy. There have been several studies that have looked at the use of everyday software packages in management processes. Within studies of strategy the focus has been particularly on Microsoft’s PowerPoint. While this might seem a rather mundane technology, as the Dilbert cartoon in Figure 3.6 illustrates, perhaps it has the potential to change the world?

Kaplan (2011) notes that PowerPoint presentations have become the dominant means of communication during both strategy development and communication, noting that the technology has both its champions and its opponents: ‘Whereas champions have promoted PowerPoint as a simple way to build persuasive presentations, critics (mainly in the popular press) have argued that it constrains expression to certain templates, forces oversimplification, and even edits thoughts’ (p. 320).

Kaplan’s research draws on social conceptions of strategy and ideas about strategy making as practice. While it might seem rather odd to focus on PowerPoint among all of the issues that need to be considered when developing a strategy, this is precisely Kaplan’s point. Because we think of strategy as something ‘BIG’ we tend to overlook the ‘small’ ways in which power is implicated within strategy-making processes on a day-to-day basis. Kaplan researched the processes of strategy making in a large telecommunications company, and found the following:

- Using PowerPoint was perceived as a way of appearing professional.

- PowerPoint was particularly adopted by new managers and those who were not in clear positions of authority.

- In the case of one new manager who did not follow the required PowerPoint template, discussion was deferred until he could return to present with the slides in the correct format.

- There was less discussion around content issues at meetings, rather participants focused on the headings and format of presentations.

- Progress was measured in volume of PowerPoint slides or decks.

Specifically with respect to power Kaplan (2011, p. 328) found that:

- Using PowerPoint correctly ‘Certifies facts that are included and deligitimizes that which are not included’.

- PowerPoint ‘Allows authors to choose whose slides and which slides to include. The “owner” of the deck has power to define boundaries’.

- Authors can control what is shared and how ‘materials can be presented in a meeting but not distributed’.

From this detailed example of PowerPoint, we now explore a research paper that examines the work of an HRD team, also drawing on ideas of social (practice) perspectives on strategy.

Activity 3.6: Exploring issues of power in HRD practice (90 minutes)